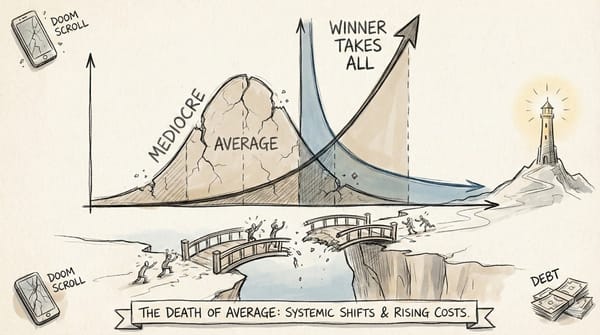

The Death of the Value Investor: Why Benjamin Graham's P/E Rule is Becoming Obsolete

Traditional value investors are terrified by the current P/E ratio of the S&P 500. But the market isn't irrational. The underlying math of capitalism has fundamentally changed, rendering old valuation models completely obsolete.

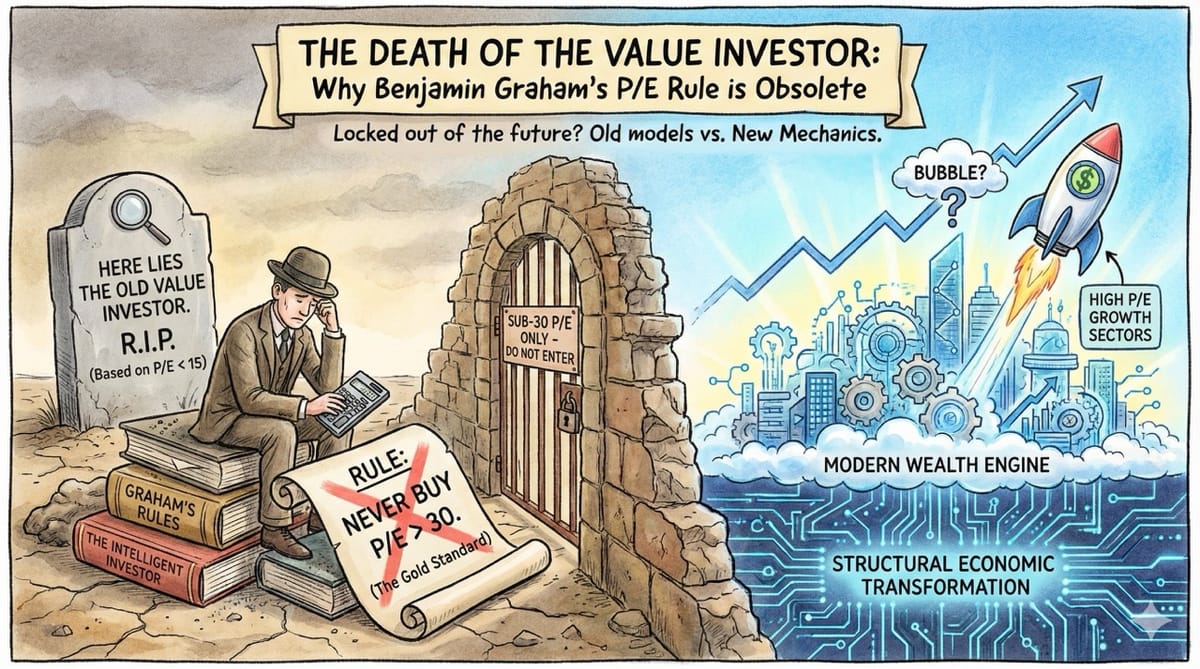

Benjamin Graham taught us to never buy a stock with a P/E ratio over 30. Today, applying that rule locks you out of the greatest wealth-creation engine in human history.

Inspiration: Looking at the S&P 500's historical P/E ratios and wondering if we are in a massive bubble. Then realizing the structural mechanics of the modern economy make the old rules completely irrelevant (between you and I, also missing out on plenty of gains due to refusing to buy over 30 PE ratios).

Benjamin Graham built the foundation of value investing on a very simple premise. You buy companies trading at low price-to-earnings multiples to guarantee a margin of safety.

For decades, a P/E ratio under 15 was the gold standard. Anything over 30 was considered dangerous speculation.

Today, applying that rigid sub-30 rule will essentially lock you out of the most profitable sectors of the global economy.

The stock market has not gone crazy. It has simply undergone a profound structural transformation that renders the old valuation models obsolete.

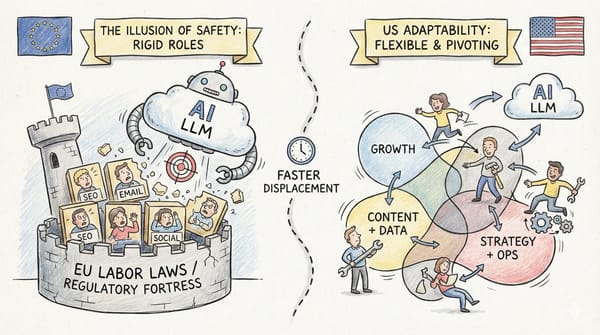

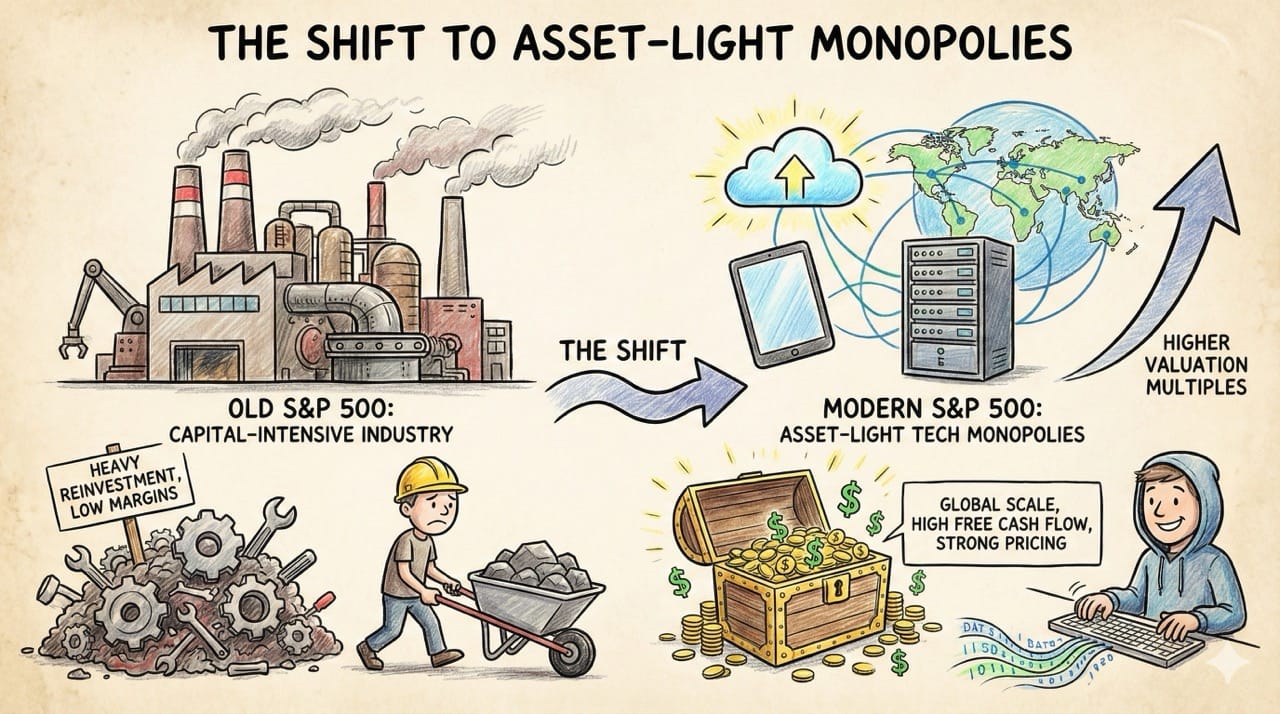

The Shift to Asset-Light Monopolies

The composition of the S&P 500 has completely transformed since Graham was writing.

In his era, the market was dominated by capital-intensive industries like heavy manufacturing, utilities, and traditional energy exploration.

These businesses required constant physical reinvestment just to maintain their operations.

This heavy capital expenditure kept their profit margins and valuation multiples relatively low.

Today, the index is heavily concentrated in technology and software monopolies. These modern giants are incredibly asset-light and can scale globally with minimal marginal costs.

They generate massive free cash flow, possess strong pricing power, and consistently deliver high returns on invested capital.

Investors naturally assign higher valuation multiples to these superior business models.

When high-multiple technology stocks make up nearly a third of the entire index, they mathematically drag the average P/E of the broader market upward.

The United States as a Global Safe Haven

We also have to look at the macroeconomic reality of global capital flows.

The United States offers unmatched market liquidity, robust property rights, and a culture of corporate efficiency.

During times of geopolitical uncertainty or global economic slowdowns, foreign capital aggressively seeks the safety of US equities.

The US economy also consistently demonstrates a higher potential growth rate than Europe or Japan.

This is largely due to its absolute edge in technological innovation. This constant, desperate influx of global capital creates a persistent premium on US asset prices.

When the whole world wants to park their money in one specific market, the baseline valuation of that market structurally shifts higher.

It becomes a premium destination, and investors gladly pay a premium price.

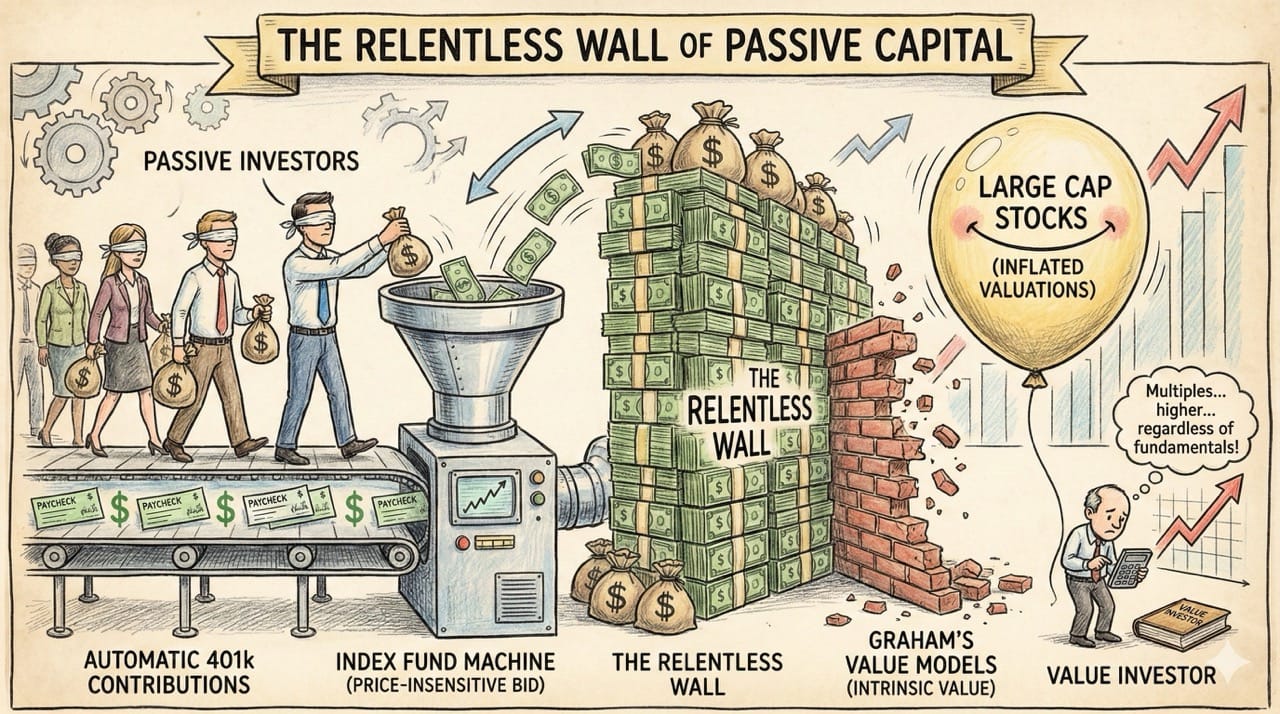

The Relentless Wall of Passive Capital

The mechanics of modern investing have fundamentally altered how price discovery works. Stock ownership in the US has skyrocketed since the 1980s.

The transition from traditional pensions to 401k retirement plans has created a relentless machine of passive investing.

Every time paychecks clear across the country, billions of dollars are automatically and blindly deployed into index funds.

This creates a continuous, price-insensitive bid under the market.

This mechanism disproportionately inflates the valuations of the largest companies in the index.

These passive funds do not care about Graham's intrinsic value models.

They simply buy the market cap weighting, pushing multiples higher regardless of underlying fundamentals.

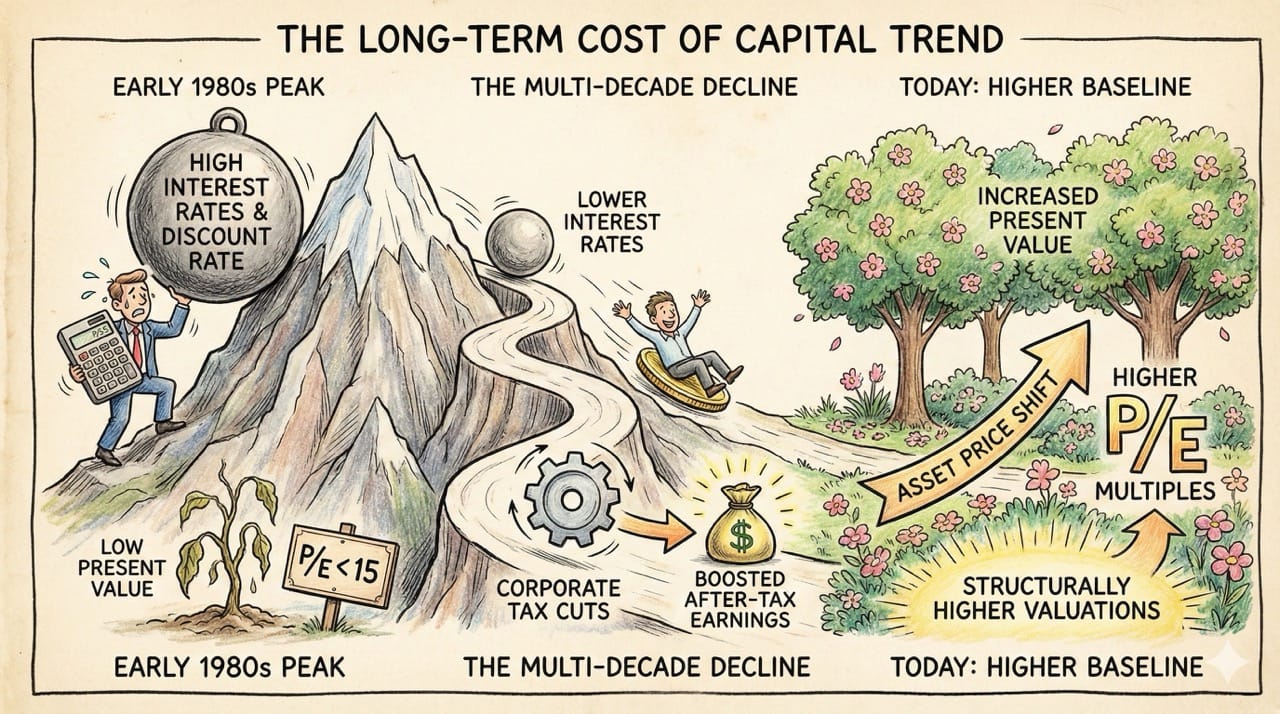

The Long-Term Cost of Capital Trend

Finally, we have to account for the mathematical relationship between interest rates and valuations.

While the recent post-pandemic era represented an extreme low for interest rates, the broader trend has been downward for over forty years.

After interest rates peaked in the early 1980s, they began a steady, multi-decade decline.

Lower interest rates reduce the discount rate applied to future corporate earnings. This mathematically increases the present value of those earnings, justifying higher P/E multiples across the board.

Furthermore, corporate tax cuts over recent decades have structurally improved after-tax earnings.

This provides yet another fundamental boost to baseline market valuations.

The cost of capital has fundamentally shifted, which means the price of assets must follow suit.

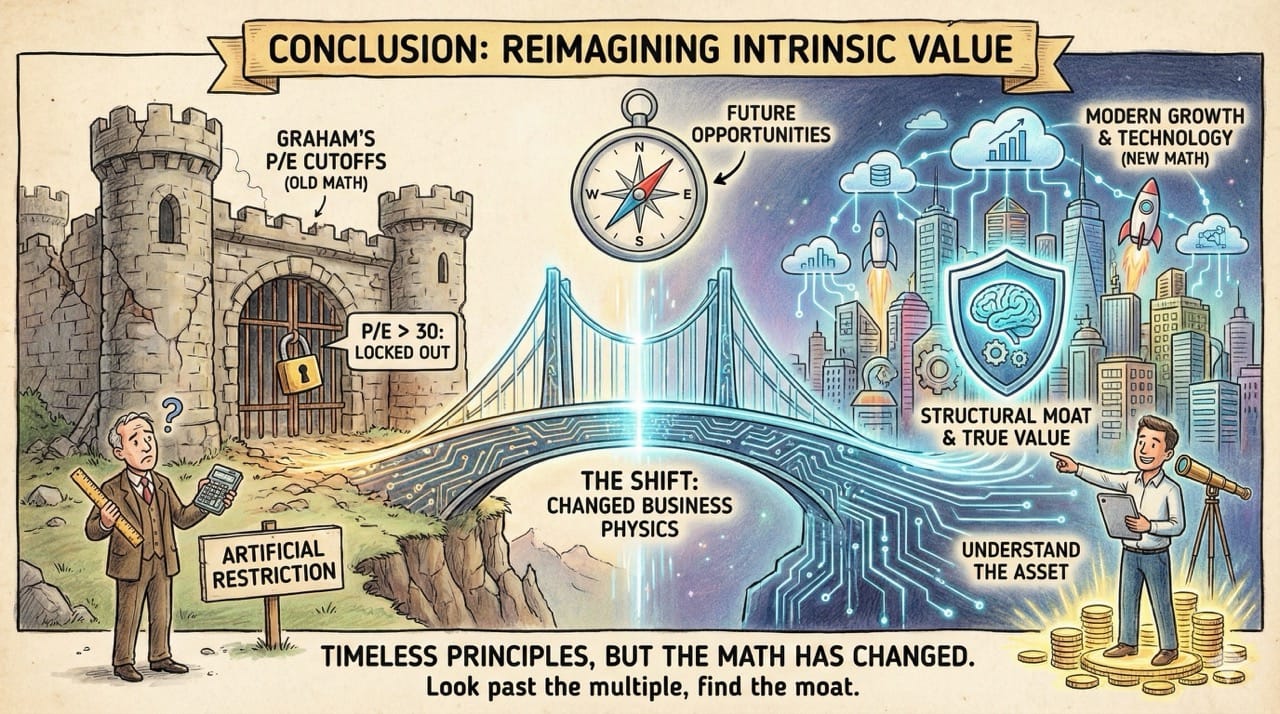

Conclusion: Reimagining Intrinsic Value

Graham's core principles of seeking intrinsic value and a margin of safety remain timeless.

However, strictly adhering to historical P/E cutoffs will artificially restrict your opportunities in a market dominated by high-growth technology.

The math of the S&P 500 has changed because the physics of business have changed. To find true value today, you have to look past the absolute multiple and understand the structural moat of the asset.